Complexity Thoughts: Issue #76

Unraveling complexity: building knowledge, one paper at a time

If you find value in #ComplexityThoughts, consider helping it grow by subscribing and sharing it with friends, colleagues or on social media. Your support makes a real difference.

→ Don’t miss the podcast version of this post: click on “Spotify/Apple Podcast” above!

Foundations of network science and complex systems

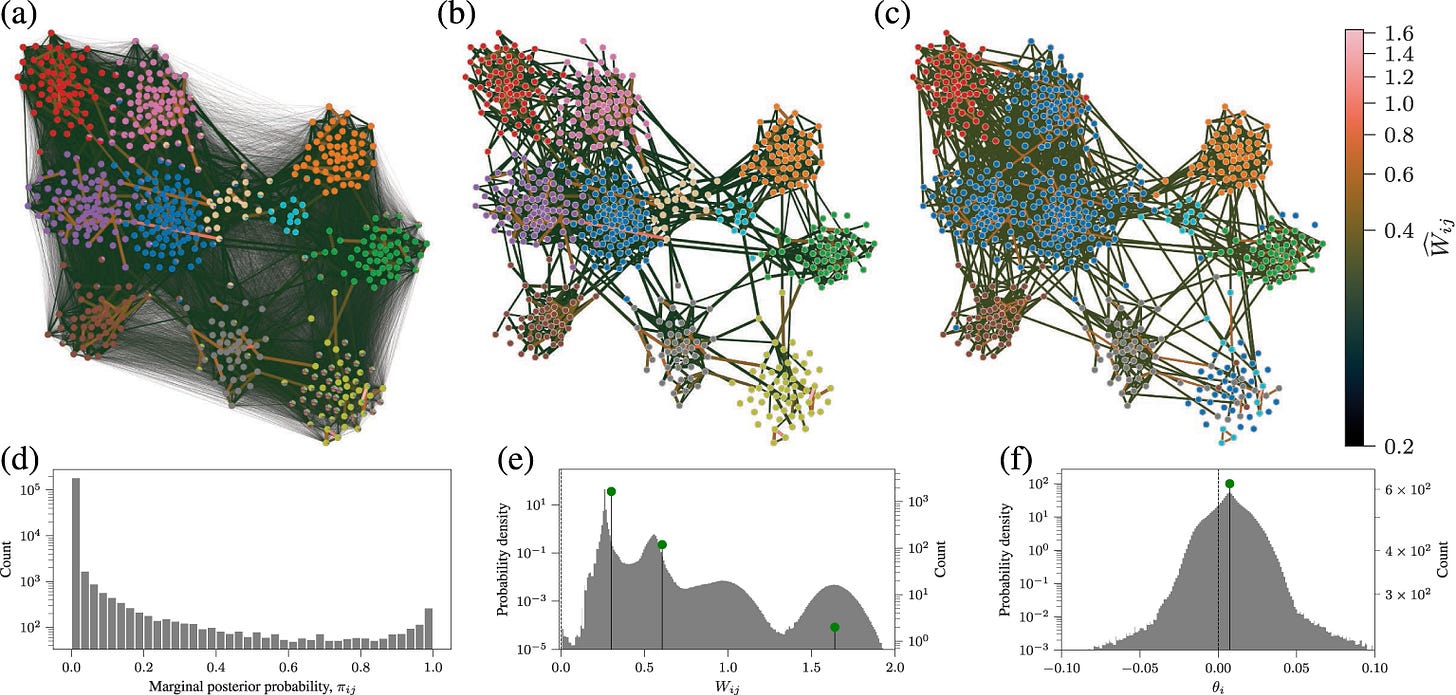

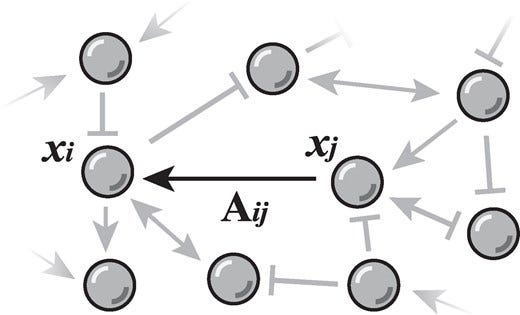

Uncertainty quantification and posterior sampling for network reconstruction

Network reconstruction is the task of inferring the unseen interactions between elements of a system, based only on their behaviour or dynamics. This inverse problem is in general ill-posed and admits many solutions for the same observation. Nevertheless, the vast majority of statistical methods proposed for this task—formulated as the inference of a graphical generative model—can only produce a ‘point estimate’, i.e. a single network considered the most likely. In general, this can give only a limited characterization of the reconstruction, since uncertainties and competing answers cannot be conveyed, even if their probabilities are comparable, while being structurally different. In this work, we present an efficient Markov-chain Monte–Carlo algorithm for sampling from posterior distributions of reconstructed networks, which is able to reveal the full population of answers for a given reconstruction problem, weighted according to their plausibilities. Our algorithm is general, since it does not rely on specific properties of particular generative models, and is specially suited for the inference of large and sparse networks, since in this case an iteration can be performed in time O(N log^2 N) for a network of N nodes, instead of O(N^2), as would be the case for a more naïve approach. We demonstrate the suitability of our method in providing uncertainties and consensus of solutions (which provably increases the reconstruction accuracy) in a variety of synthetic and empirical cases.

Evolution

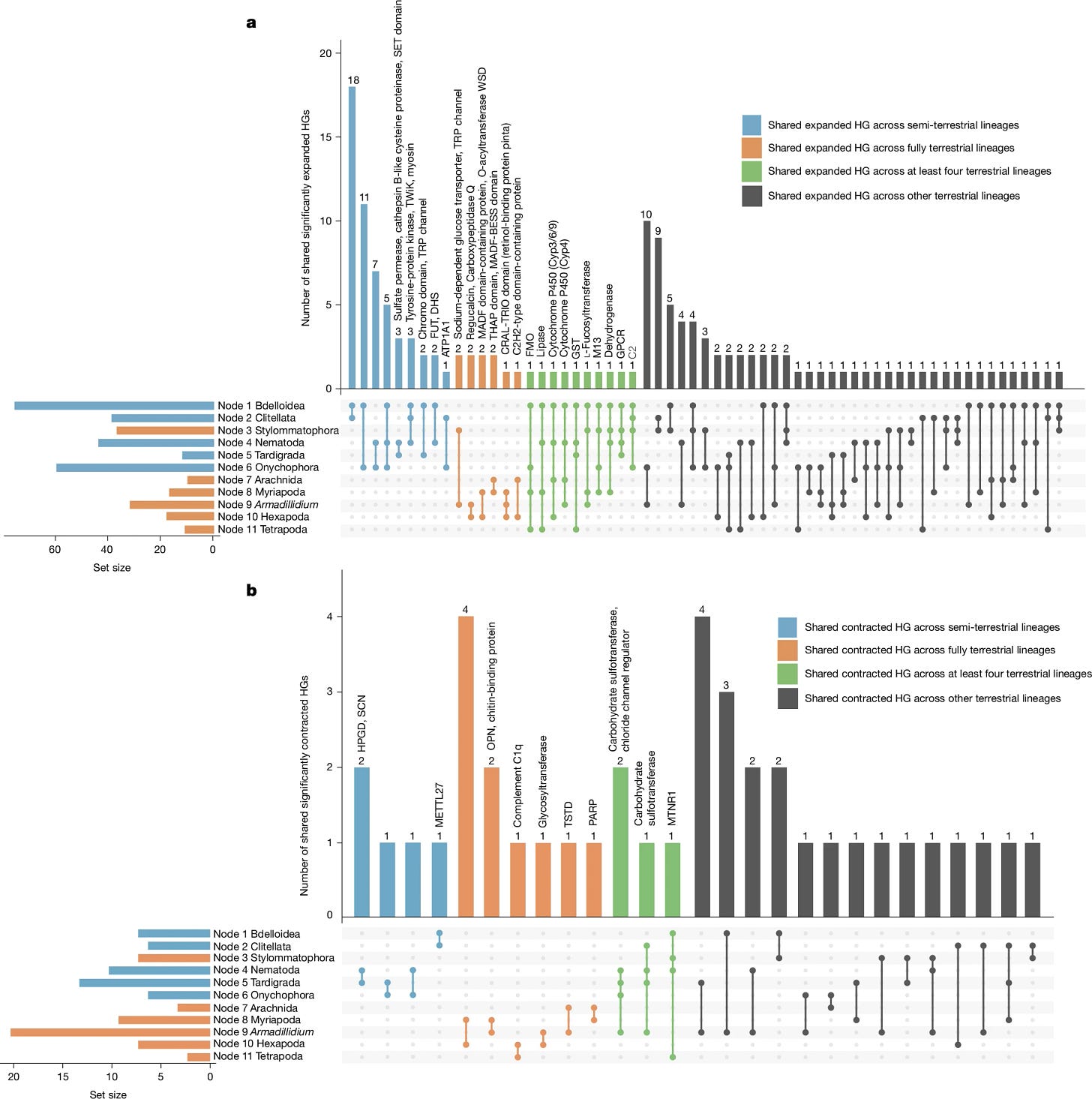

Convergent genome evolution shaped the emergence of terrestrial animals

The challenges associated with the transition of life from water to land are profound1, yet they have been met in many distinct animal lineages2,3,4,5. These constitute a series of independent evolutionary experiments from which we can decipher the role of contingency versus convergence in the adaptation of animal genomes. Here we compare 154 genomes from 21 animal phyla and their outgroups to reconstruct the protein-coding content of the ancestral genomes linked to 11 animal terrestrialization events, and to produce a timescale of terrestrialization. We uncover distinct patterns of gene gain and loss underlying each transition to land, but similar biological functions emerged recurrently pointing to specific adaptations as key to life on land. We show that semi-terrestrial species evolved convergent functional patterns, in contrast with fully terrestrial lineages that followed different paths to land. Our timeline supports three temporal windows of land colonization by animals during the last 487 million years, each associated with specific ecological contexts. Although each lineage exhibits distinct adaptations, there is strong evidence of convergent genome evolution across the animal kingdom suggesting that, in large part, adaptation to life on land is predictable, linking genes to ecosystems.

Ecosystems and Behavioral Ecology

Understanding the laws that determine species distributions is essential for predicting how plant species will respond to climate change. Here, we examine the macroecological relationship between geographic range size, climatic niche breadth, and variation in ecological dominance, three fundamental properties that shape biodiversity patterns. Climatic niche breadth represents the range of climatic conditions a species can tolerate, while geographic range size defines the spatial extent of its populations. Using a global dataset of major plant groups, we demonstrate that species that occupy larger geographic ranges tend to have broader climatic niches and are more likely to achieve high local abundances. These findings provide key insights into species’ vulnerability to environmental change and the processes that structure biodiversity at global scales.

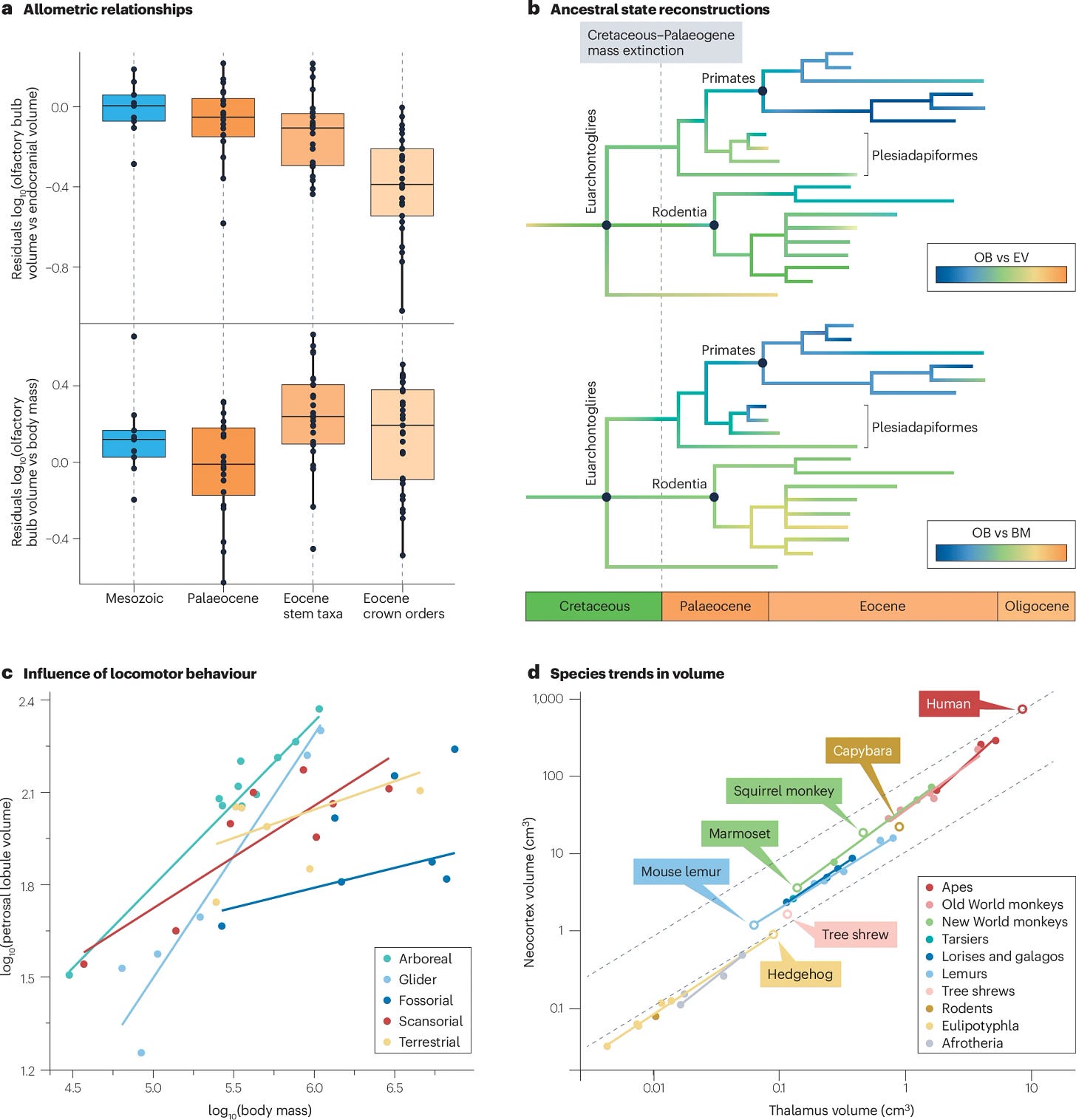

The functional adaptations of mammalian brain structures through a behavioural ecology lens

Mammal brains scale in two main ways:

Concerted evolution treats the brain as an integrated system: shared developmental programs make regions grow together, so larger brains show predictable allometries (e.g., the neocortex expands faster than the thalamus). Evidence supports this, but it struggles to explain targeted adaptations.

Mosaic evolution treats regions as semi-independent modules: selection can enlarge circuits for specific behaviors while others stay similar, often in linked functional sets (vision, smell). Bats vs primates show a sensory tradeoff, echoed in fossils.

I love the interdisciplinary approaches to understand how brain evolved, and why. I have written a short essay about this, here:

The organization of the extant mammalian brain is influenced by development, evolutionary history and the environment. Ecological adaptations specifically have had a major role in shaping the structures and associated functions of the mammalian brain. Although general organization of the brain is relatively conserved in modern mammals, throughout millions of years of evolution mammals have acquired diverse sensory and nervous system adaptations as they invaded new ecological niches. Here, we synthesize palaeontological and neurobiological evidence on mammalian brain structure evolution, the mechanisms behind the observed variation in the size and organization of brain structures, and the effect of behavioural ecology on the evolution of brain functions and associated structures. Neuroecology has advanced greatly over the past 40 years and is now unravelling the complex relationship between specific behaviours and brain organization and function. Relying on different types of data, comparative neurobiologists and palaeontologists strive to answer similar questions about brain evolution, benefiting from a synergistic approach. We conclude this Review by outlining outstanding questions regarding the relationships between structure, function, behaviour and evolution that deserve future research attention, and propose methodologies and approaches to help to resolve these problems.

Symmetry breaking in a metapopulation model with fitness-dependent dispersal

This study investigates the emergence of symmetry-breaking dynamics and the associated bifurcation behavior in an identically coupled Rosenzweig-MacArthur model with fitness-dependent dispersal between patches. We identify the occurrence of a symmetry-breaking (SB) state, characterized by the difference in the amplitude of oscillations across patches, signifying a form of desynchronization that supports species persistence. As the predator dispersal rate is varied, the SB state undergoes a sequence of dynamical transitions, alternating between chaotic symmetry breaking (CSB) and periodic symmetry breaking (PSB) states, and it includes the emergence of periodic windows that occur within chaotic windows across the dispersal rate. The alternating chaotic and periodic nature of SB dynamics is confirmed with the help of Lyapunov exponent analysis. In addition to the SB state, we observed antiphase synchronized (APS) and in-phase synchronized (IPS) states. To further understand the impact of initial conditions on distinct dynamical outcomes, we explore the basins of attraction within multistable regions. Finally, the stability of the APS, PSB, and IPS states is analyzed using Floquet analysis.

Biological Systems

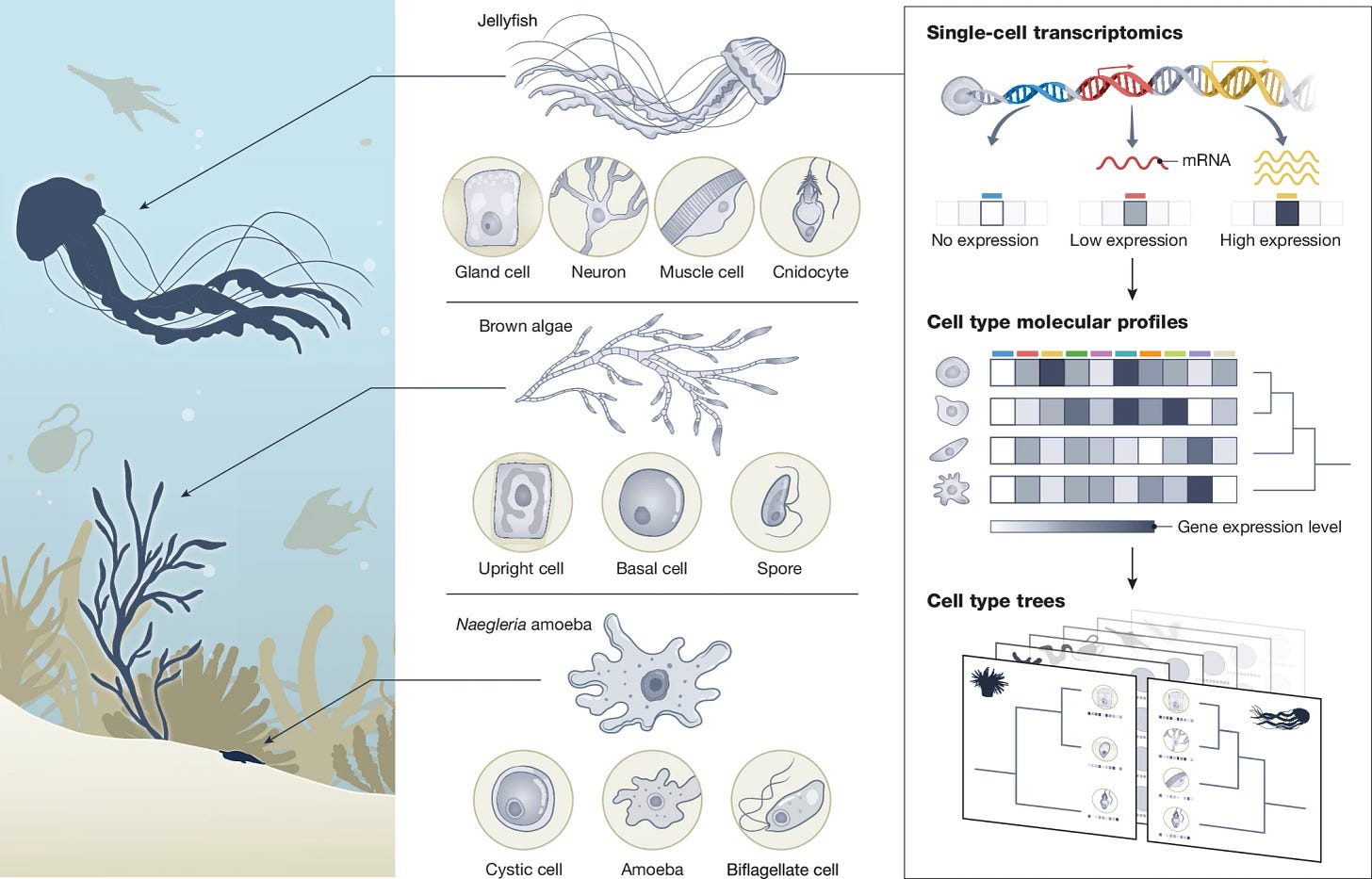

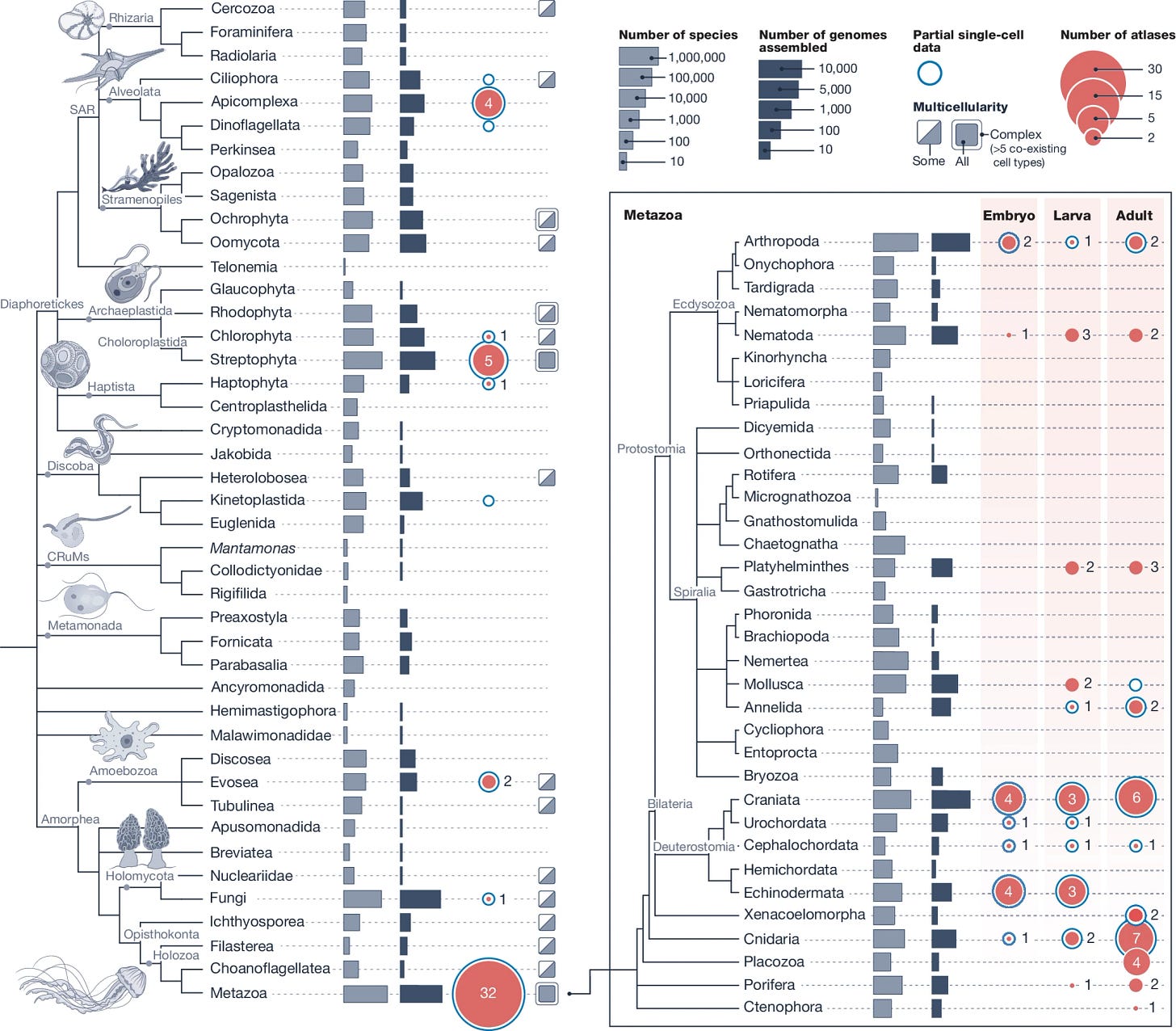

The Biodiversity Cell Atlas: mapping the tree of life at cellular resolution

How cool is this? I cannot wait for the outcomes of this project.

Cell types are fundamental functional units that can be traced across the tree of life. Rapid advances in single-cell technologies, coupled with the phylogenetic expansion in genome sequencing, present opportunities for the molecular characterization of cells across a broad range of organisms. Despite these developments, our understanding of eukaryotic cell diversity remains limited and we are far from decoding this diversity from genome sequences. Here we introduce the Biodiversity Cell Atlas initiative, which aims to create comprehensive single-cell molecular atlases across the eukaryotic tree of life. This community effort will be phylogenetically informed, rely on high-quality genomes and use shared standards to facilitate comparisons across species. The Biodiversity Cell Atlas aspires to deepen our understanding of the evolution and diversity of life at the cellular level, encompassing gene regulatory programs, differentiation trajectories, cell-type-specific molecular profiles and inter-organismal interactions.

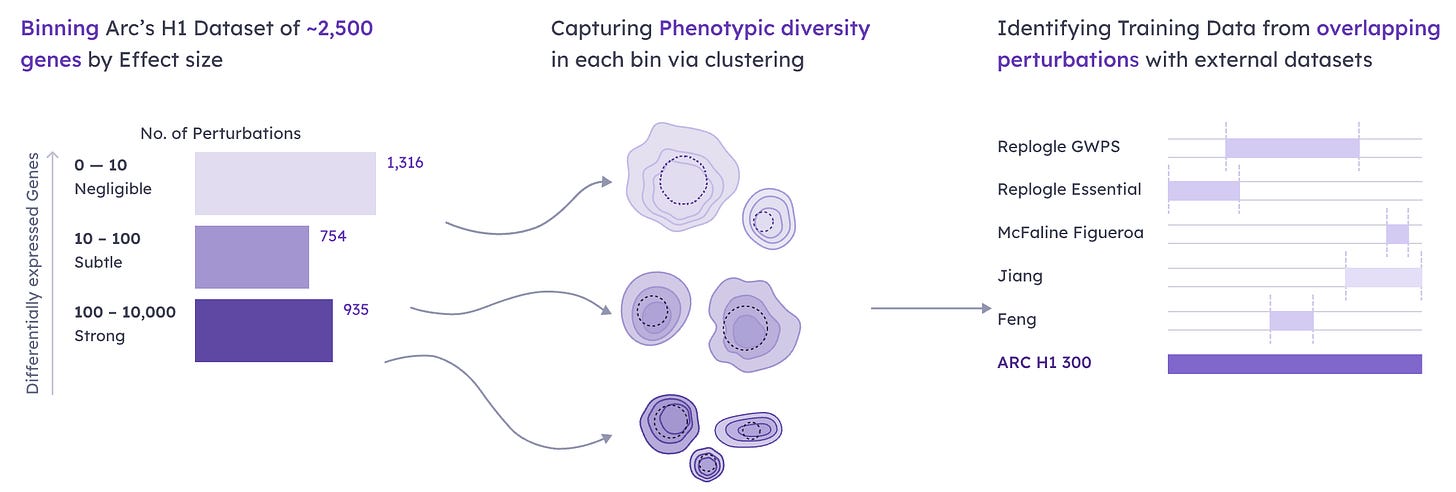

AI cell models could transform biomedicine—if they work as promised.

AI “virtual cells” aim to predict how real cells react (gene edits, drugs, disease) by learning from massive single-cell datasets. The challenge: cells are multi-omic, spatial and dynamic, but most models see only gene-expression snapshots; data are scattered, nonstandard and still sparse.

Harder still is proving skill: zero-shot tests sometimes show simple baselines beat flashy foundation models, motivating standardized benchmarks like the Virtual Cell Challenge. If solved, virtual cells could speed drug screening and personalize therapy, and help design engineered cells and tissues.

Role of frustrations in cell reprogramming

The cell fate transition is a fundamental characteristic of living organisms. By introducing external perturbations, it is possible to artificially intervene in cell fate and trigger cell reprogramming. Revealing the general principle underlying the induced phenotypic reshaping of cell populations remains a central focus in the field of cell biology. In this study, we investigate the energetic and dynamic features of induced cell phenotypic transition from differentiated somatic state to pluripotent state by constructing a Boolean genetic network model. The simulation and experimental results highlight the critical role of genetic frustration in initiating cell fate transitions, although the two ending phenotypic states are typically featured by minimal frustration. In addition, the altered gene expression profiles exhibit a scale-free distribution, suggesting that there exist a small number of critical genes responsible for the cell fate transition. This study provides important insights into the dynamic principles governing effective cell reprogramming caused by artificial or exogenous interventions.

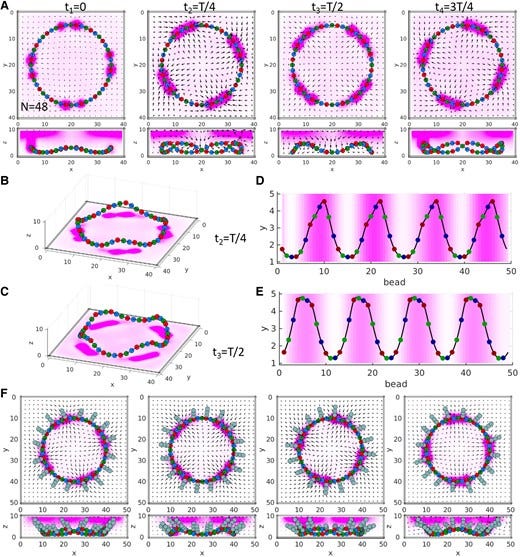

Chemical signaling in reaction networks generates corresponding mechanical impulses

Chemical reaction networks (CRNs) in the body are directed pathways that transmit reagents to reactive sites and trigger chemical processes, which ultimately instigate the appropriate physical activity. Typically, models for CRNs do not describe the coupling among chemistry, hydrodynamics and fluid–structure interactions that inherently arise in fluids. Herein, we develop a model that describes the above interrelated physicochemical behavior and show that chemical transport in a CRN spontaneously gives rise to transduction of chemistry into mechanical work, to form a complementary chemo-mechanical network (CMN). To simulate CRNs, we use the repressilator model, a reaction pathway involving biomimetic feedback loops. The encompassing material system is formed from an ordered array of enzyme-coated beads that are interlinked to form a flexible network. Coupling of chemistry and hydrodynamics occurs through the solutal buoyancy mechanism where variations in chemical concentration drive the fluid motion that deforms the flexible network of beads. Consequently, this system displays chemo-mechanical transduction as chemical signals in the CRN are converted to mechanical action. Using this model, we design materials systems encompassing CRNs that spontaneously generate CMNs, which perform the mechanical work of transporting particles or morphing the structure of the elastic network. The propagation of chemical signals along CMN that lead to mechanical actions mimic a nervous system, which transmits signals that instruct a responsive musculature.

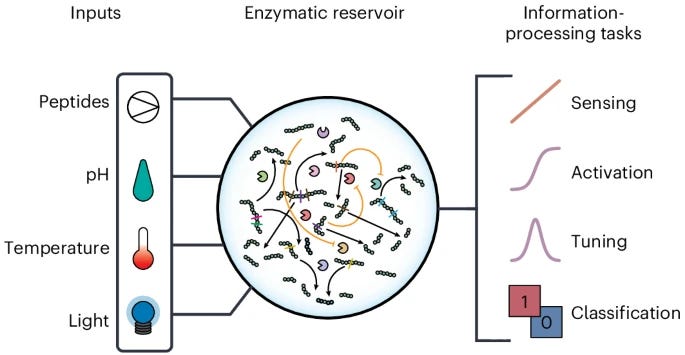

A recursive enzymatic competition network capable of multitask molecular information processing

Very cool. Read also this post.

Living cells understand their environment by combining, integrating and interpreting chemical and physical stimuli. Despite considerable advances in the design of enzymatic reaction networks that mimic hallmarks of living systems, these approaches lack the complexity to fully capture biological information processing. Here we introduce a scalable approach to design complex enzymatic reaction networks capable of reservoir computation based on recursive competition of substrates. This protease-based network can perform a broad range of classification tasks based on peptide and physicochemical inputs and can simultaneously perform an extensive set of discrete and continuous information processing tasks. The enzymatic reservoir can act as a temperature sensor from 25 °C to 55 °C with 1.3 °C accuracy, and performs decision-making, activation and tuning tasks common to neurological systems. We show a possible route to temporal information processing and a direct interface with optical systems by demonstrating the extension of the network to incorporate sensitivity to light pulses. Our results show a class of competition-based molecular systems capable of increasingly powerful information-processing tasks.

→ Please, remind that if you find value in #ComplexityThoughts, you might consider helping it grow by subscribing, or by sharing it with friends, colleagues or on social media. See also this post to learn more about this space.