How modern “now-ism“ can accelerate crises in climate, finance and ecosystems

Slowing change may be our last line of defense

If you find value in #ComplexityThoughts, consider helping it grow by subscribing and sharing it with friends, colleagues or on social media. Your support makes a real difference.

→ Don’t miss the podcast version of this post: click on “Spotify/Apple Podcast” above!

Disclaimer: this post started as a regular Issue (#67, to be precise). But I enjoyed reading the papers and finding a way to describe the topic so much that it turned into a hybrid, something between an Issue and a Short Essay. I hope you will enjoy it as usual.

Sudden, often irreversible, shifts in complex systems are known as tipping points.

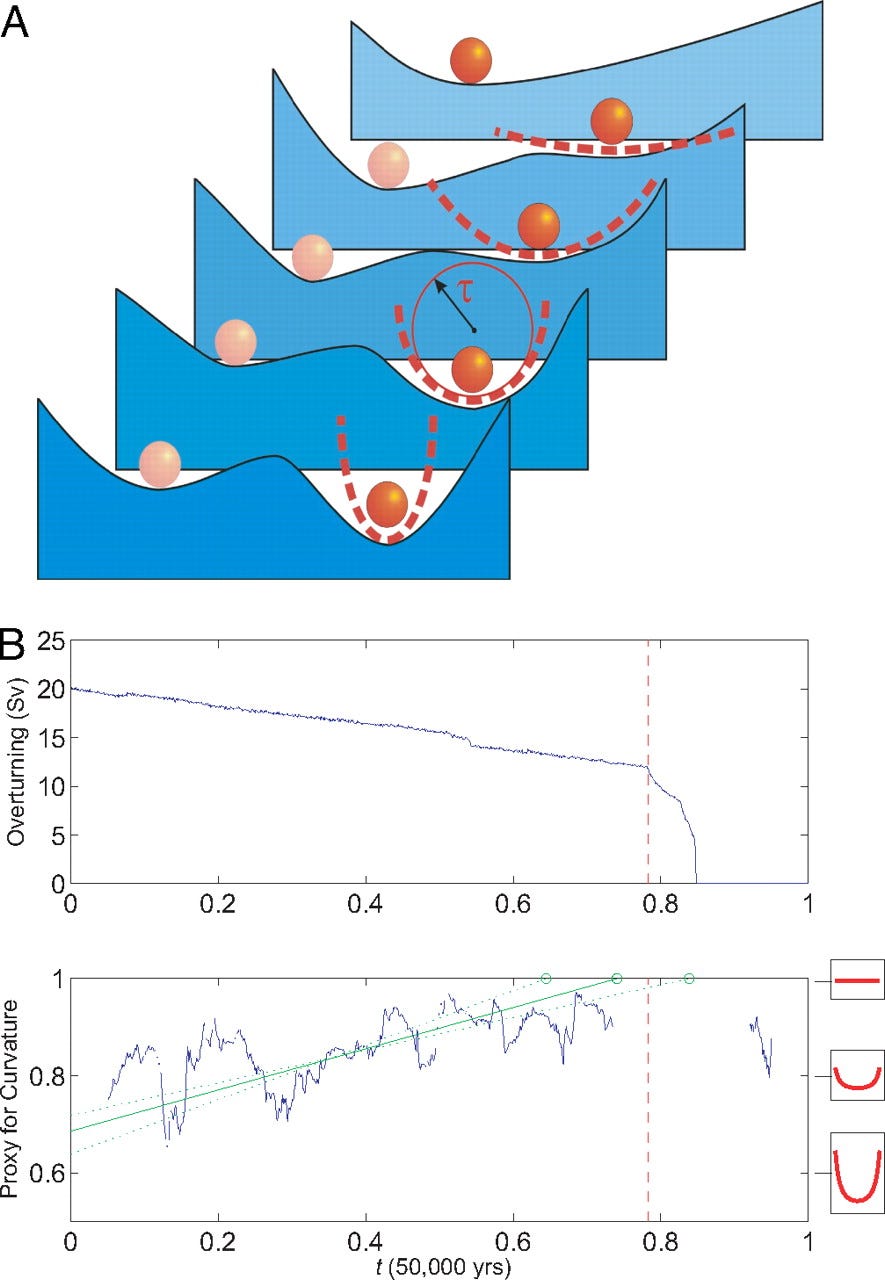

The most familiar kind is bifurcation-induced tipping (or B-tipping), where the system’s stable state disappears when a control parameter (e.g., temperature) crosses a threshold. Once you pass this critical point, no matter how carefully you step back, the system won’t return back to the previous conditions.

This type of catastrophic dynamics can affect every complex system. Accordingly, the question is: can we anticipate them, e.g., by identifying and monitoring early-warning signals?

In a fantastic review article, Scheffer et al (2009) made an effort to describe such signatures for a variety of systems:

Complex dynamical systems, ranging from ecosystems to financial markets and the climate, can have tipping points at which a sudden shift to a contrasting dynamical regime may occur. Although predicting such critical points before they are reached is extremely difficult, work in different scientific fields is now suggesting the existence of generic early-warning signals that may indicate for a wide class of systems if a critical threshold is approaching.

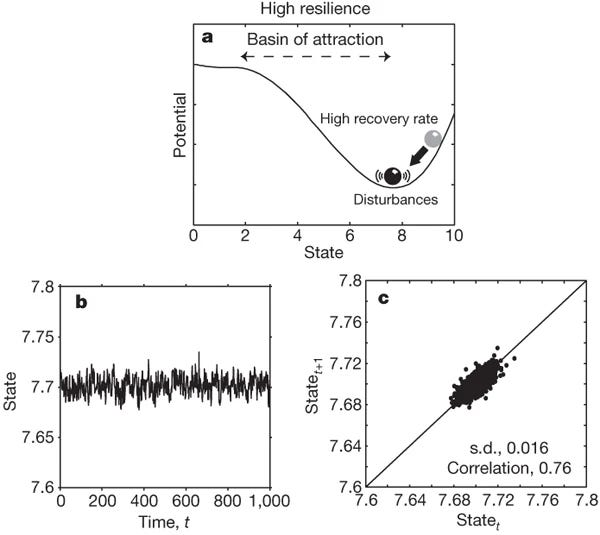

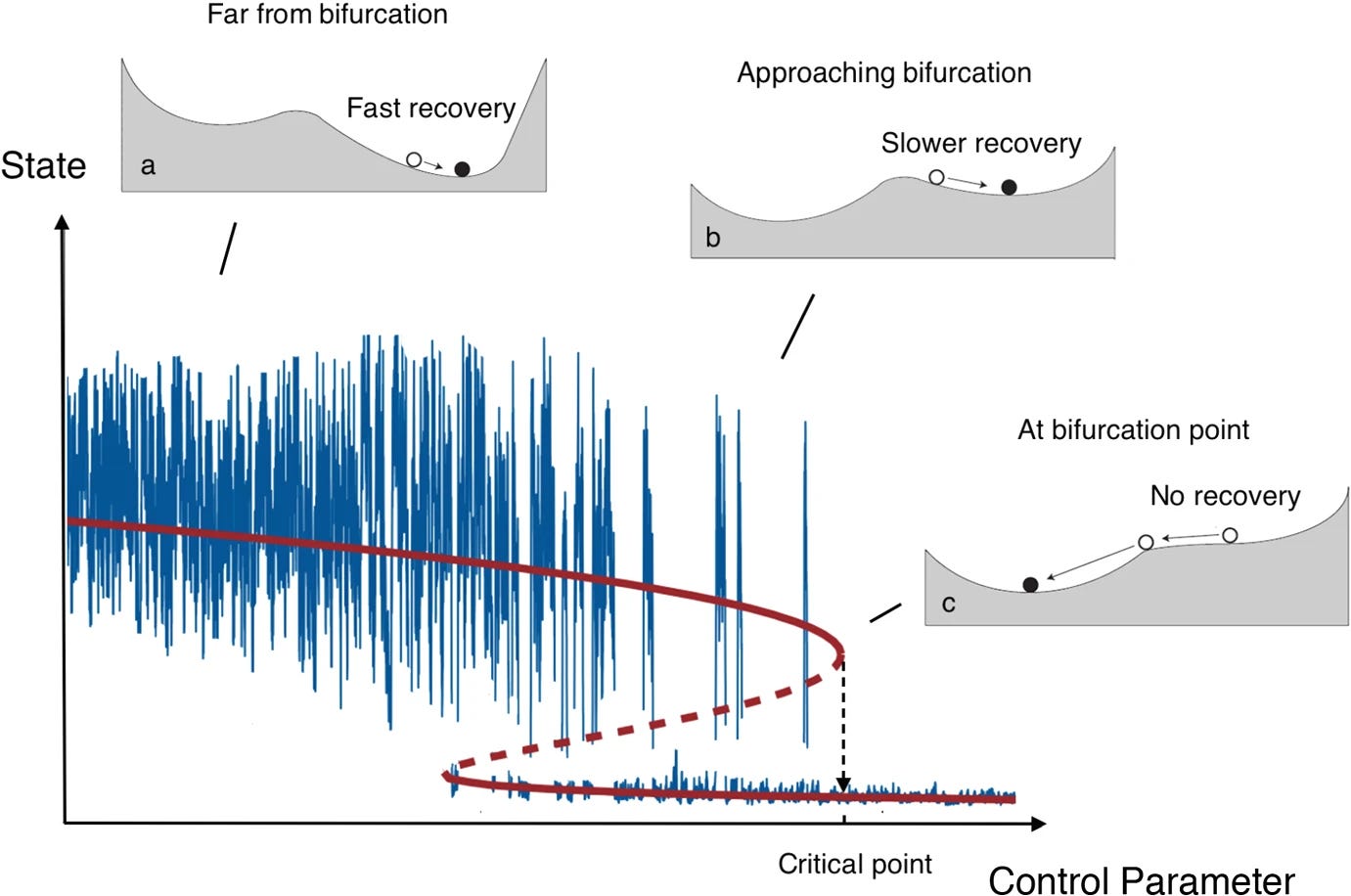

The case of high resilience

Far from a bifurcation (a) the system is highly resilient. This resilience shows up in two ways:

the basin of attraction is wide, meaning the system can absorb large shocks without leaving its stable state;

the recovery rate from small perturbations is fast.

The result is that, under random (stochastic) disturbances, the dynamics look relatively stable, with low correlation between the system’s state at successive time points (b, c).

The case of low resilience

Close to a bifurcation (d), conversely, resilience weakens:

the basin of attraction shrinks, making the system more fragile;

the recovery rate from disturbances slows down.

This phenomenon, known as “critical slowing down”, describes systems developing a longer memory of perturbations. In a stochastic environment, this shows up as larger fluctuations (higher standard deviation) and stronger correlations between consecutive states (e, f).

This is the case of most interest, of course, and also the most problematic.

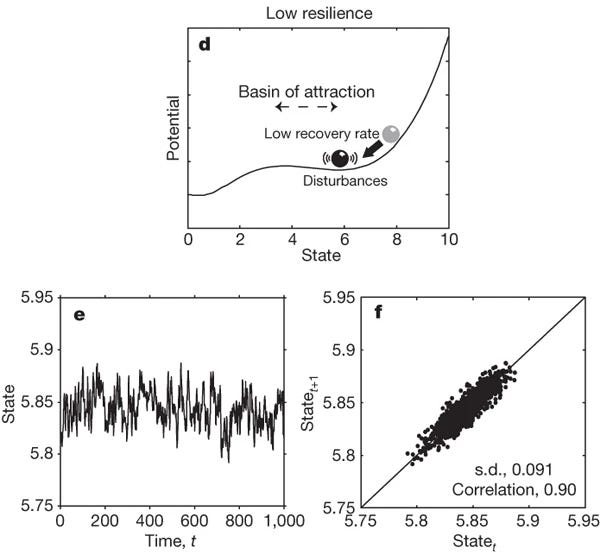

“Ecosystems may undergo a predictable sequence of self-organized spatial patterns as they approach a critical transition”

Why?

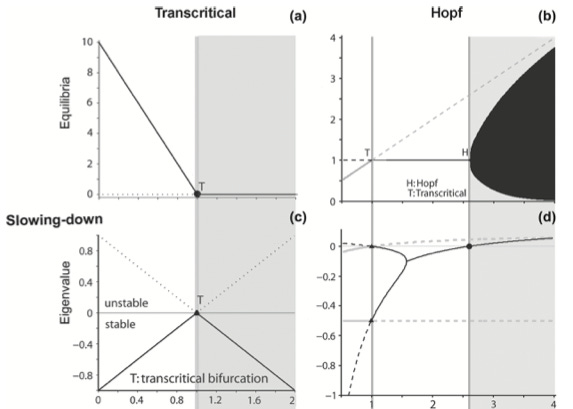

From a mathematical point of view, critical slowing down arises because the system’s recovery rate from perturbations is determined by the dominant eigenvalue of the linearized dynamics around equilibrium. For simplicity, let us consider a one-dimensional system

with equilibrium x*, such that f(x*) = 0. A small perturbation ε evolves according to

where λ is the dominant eigenvalue. The associated potential landscape, centered around the equilibrium, is

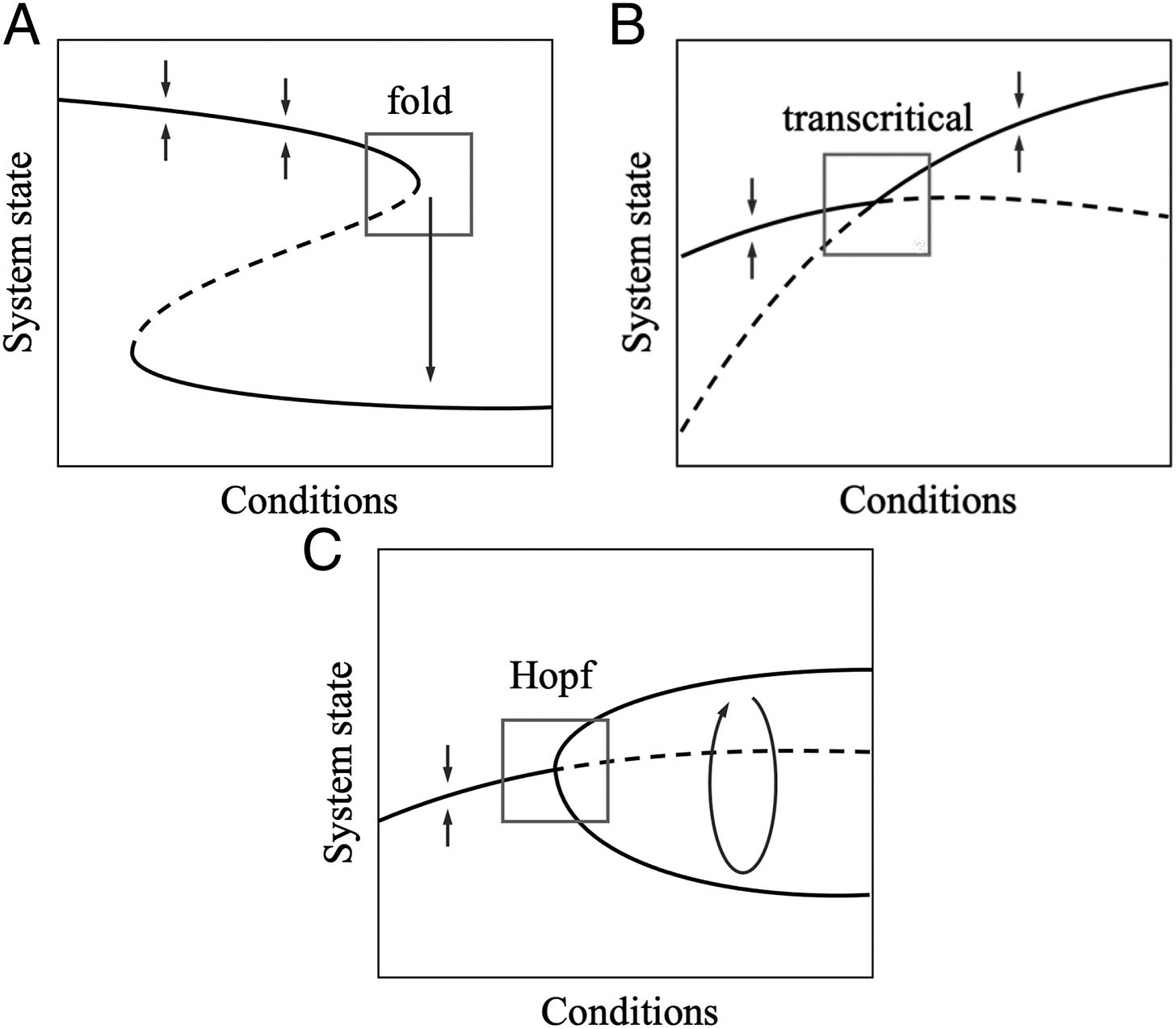

Let us not that, far from a bifurcation, λ is negative and sufficiently large in magnitude, so perturbations decay quickly back to equilibrium and the linear term dominates. However, as the system approaches a bifurcation (such as fold, Hopf, or transcritical), λ tends to 0: this reduces the restoring force, flattens the potential landscape and slows down recovery from disturbances.

That’s why this vanishing eigenvalue explains why critical slowing down emerges as an early-warning signal near bifurcations.

What are the advantages and disadvantages?

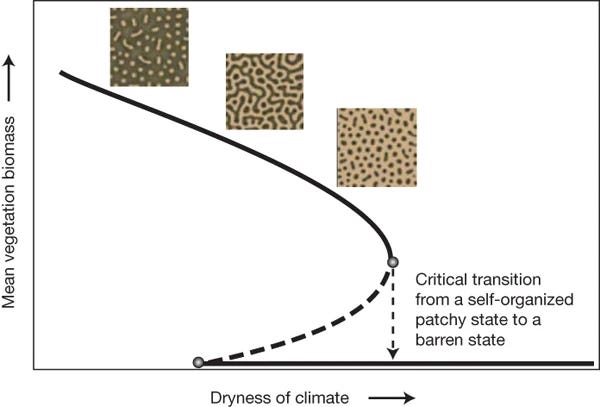

For less pathological systems, the hints that a system is approaching a tipping point can be operationally inspected as follows:

Increased autocorrelation: as critical slowing down occurs, the system's intrinsic rates of change decrease, making its state at any given moment more similar to its past state. This “memory” effect leads to an increase in autocorrelation in the fluctuations.

Increased variance: critical slowing down also causes the impacts of shocks to decay more slowly, accumulating their effect and thereby increasing the variance of the state variable.

If we do not restrict our interest to critical slowing down, we could also consider the following signatures:

Increased skewness: in catastrophic bifurcations (like fold bifurcations), an unstable equilibrium approaches the stable attractor from one side, causing the system to live longer in its vicinity where rates of change are lower, leading to an increase in skewness in the distribution of states.

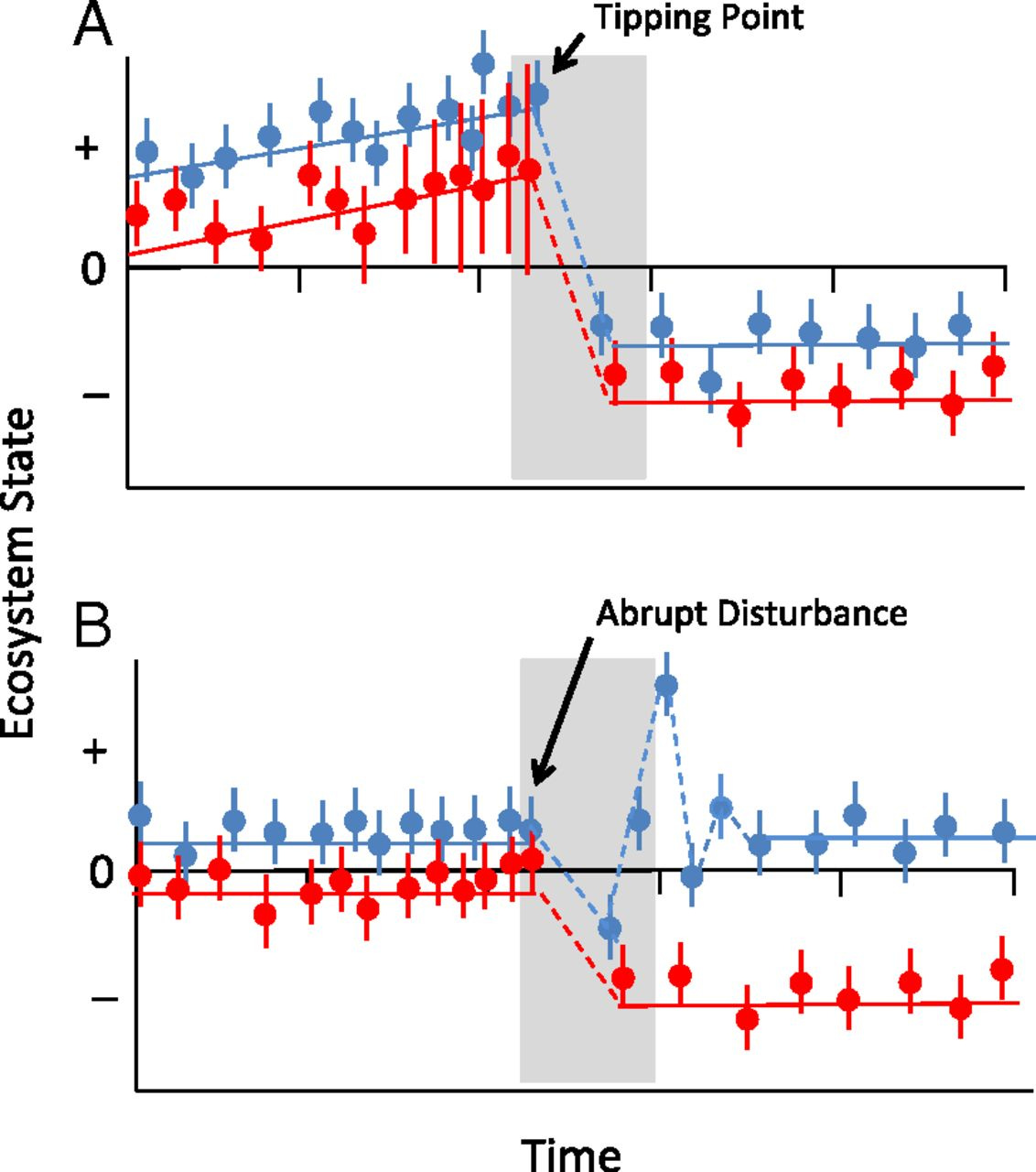

Flickering and bimodality: if stochastic forcing is strong enough, the system may oscillate between the basins of attraction of two alternative states as it enters the bistable region before a bifurcation. This flickering can be observed as increased variance, skewness and bimodality in the frequency distribution of states.

On the one hand, if a sudden shift is caused by an extreme event or a rapid, permanent change in external conditions, rather than a gradual approach to a threshold, early-warning signals may not be detectable, leading to false negatives.

On the other hand, a perceived early-warning signal might not be due to an approaching bifurcation but rather by chance or confounding trends within the system or its external environment, leading to false positives.

“Our results show that slowing down generally happens in situations where a system is becoming increasingly sensitive to external perturbations, independently of whether the impeding change is catastrophic or not. These results highlight that indicators specific to catastrophic shifts are still lacking” — Kefi et al (2012)

The literature on the study of tipping points in climate, finance, ecology, and even social system is too vast to be contained in this simple post. Someone else did a great job to this aim: see Milkoreit et al, 2018 for socio-ecological systems, Lenton, 2013 for environmental systems, as well as Scheffer et al, 2012.

Very recently, I have read the papers mentioned below to prepare a presentation about this topic, including other forms of tipping points, such as the R-tipping. In fact, not all tipping needs a critical threshold: sometimes the speed itself (i.e., the rate of change) is what matters. This is known as rate-induced tipping (or just R-tipping).

Take home message

In the end, what the study of tipping points teaches us is that resilience is not only about the limits of systems, but also about the pace at which we push them. Our culture of “now-ism” — the relentless drive for immediate returns, rapid growth and short-term fixes — accelerates us toward thresholds where recovery might no longer be possible.

Whether in climate, finance or ecosystems, the faster we move, the greater the risk that we outrun the capacity of complex systems to adapt, triggering sudden and irreversible change. If slowing down feels counterintuitive in a world obsessed with speed, it may in fact be our last line of defense against collapse.

Further reading

Ecosystems

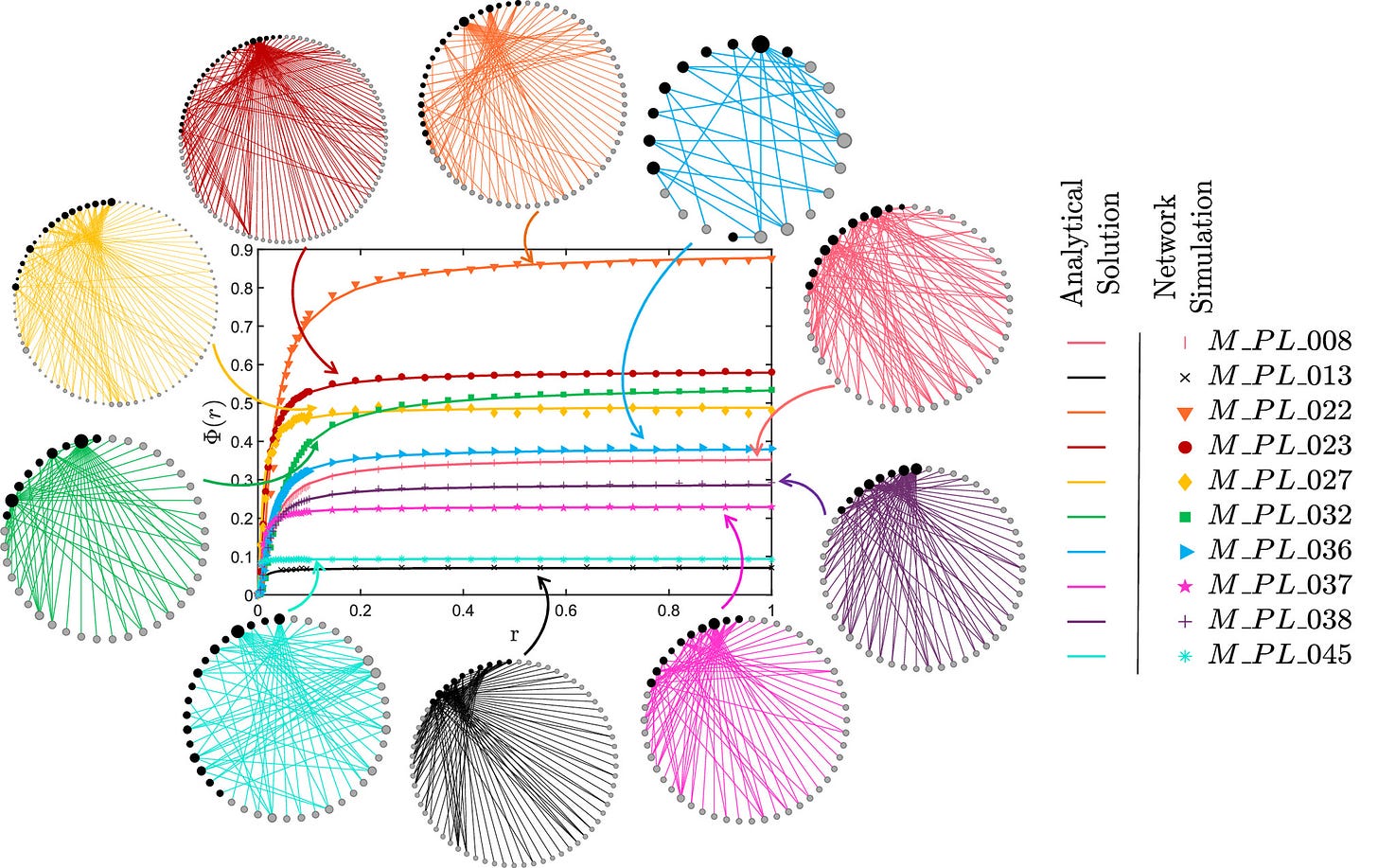

Predicting tipping points in mutualistic networks through dimension reduction

Complex systems in many fields, because of their intrinsic nonlinear dynamics, can exhibit a tipping point (point of no return) at which a total collapse of the system occurs. In ecosystems, environmental deterioration can lead to evolution toward a tipping point. To predict tipping point is an outstanding and extremely challenging problem. Using complex bipartite mutualistic networks, we articulate a dimension reduction strategy and establish its general applicability to predicting tipping points using a large number of empirical networks. Not only can our reduced model serve as a paradigm for understanding the tipping point dynamics in real world ecosystems for safeguarding pollinators, the principle can also be extended to other disciplines to address critical issues, such as resilience and sustainability.

Read also this commentary accompanying the paper.

“a framework to study tipping points not limited to plant–pollinator systems but across a variety of complex systems”

Complex networked systems ranging from ecosystems and the climate to economic, social, and infrastructure systems can exhibit a tipping point (a “point of no return”) at which a total collapse of the system occurs. To understand the dynamical mechanism of a tipping point and to predict its occurrence as a system parameter varies are of uttermost importance, tasks that are hindered by the often extremely high dimensionality of the underlying system. Using complex mutualistic networks in ecology as a prototype class of systems, we carry out a dimension reduction process to arrive at an effective 2D system with the two dynamical variables corresponding to the average pollinator and plant abundances. We show, using 59 empirical mutualistic networks extracted from real data, that our 2D model can accurately predict the occurrence of a tipping point, even in the presence of stochastic disturbances. We also find that, because of the lack of sufficient randomness in the structure of the real networks, weighted averaging is necessary in the dimension reduction process. Our reduced model can serve as a paradigm for understanding and predicting the tipping point dynamics in real world mutualistic networks for safeguarding pollinators, and the general principle can be extended to a broad range of disciplines to address the issues of resilience and sustainability.

Rate-induced tipping in complex high-dimensional ecological networks

Human activities are having increasingly negative impacts on natural systems, and it is of interest to understand how the “pace” of parameter change may lead to catastrophic consequences. This work studies the phenomenon of rate-induced tipping (R-tipping) in high-dimensional ecological networks, where the rate of parameter change can cause the system to undergo a tipping point from healthy survival to extinction. A quantitative scaling law between the probability of R-tipping and the rate was uncovered, with a striking and devastating consequence: In order to reduce the probability, parameter changes must be slowed down to such an extent that the rate practically reaches zero. This may pose an extremely significant challenge in our efforts to protect and preserve the natural environment.

In an ecosystem, environmental changes as a result of natural and human processes can cause some key parameters of the system to change with time. Depending on how fast such a parameter changes, a tipping point can occur. Existing works on rate-induced tipping, or R-tipping, offered a theoretical way to study this phenomenon but from a local dynamical point of view, revealing, e.g., the existence of a critical rate for some specific initial condition above which a tipping point will occur. As ecosystems are subject to constant disturbances and can drift away from their equilibrium point, it is necessary to study R-tipping from a global perspective in terms of the initial conditions in the entire relevant phase space region. In particular, we introduce the notion of the probability of R-tipping defined for initial conditions taken from the whole relevant phase space. Using a number of real-world, complex mutualistic networks as a paradigm, we find a scaling law between this probability and the rate of parameter change and provide a geometric theory to explain the law. The real-world implication is that even a slow parameter change can lead to a system collapse with catastrophic consequences. In fact, to mitigate the environmental changes by merely slowing down the parameter drift may not always be effective: Only when the rate of parameter change is reduced to practically zero would the tipping be avoided. Our global dynamics approach offers a more complete and physically meaningful way to understand the important phenomenon of R-tipping.

Earth Systems

I have arranged the following papers in the way they should be read, although I have discovered them in a different ordering.

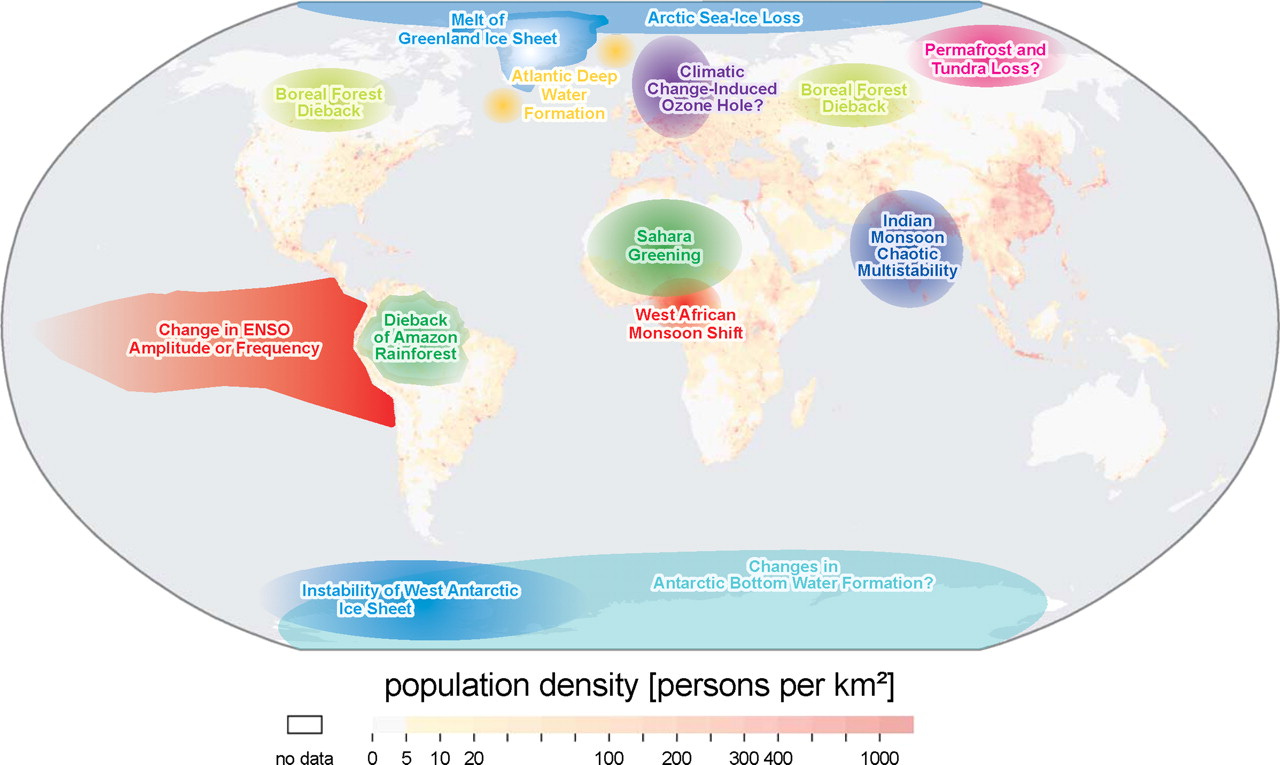

Early warning of climate tipping points

A climate 'tipping point' occurs when a small change in forcing triggers a strongly nonlinear response in the internal dynamics of part of the climate system, qualitatively changing its future state. Human-induced climate change could push several large-scale 'tipping elements' past a tipping point. Candidates include irreversible melt of the Greenland ice sheet, dieback of the Amazon rainforest and shift of the West African monsoon. Recent assessments give an increased probability of future tipping events, and the corresponding impacts are estimated to be large, making them significant risks. Recent work shows that early warning of an approaching climate tipping point is possible in principle, and could have considerable value in reducing the risk that they pose.

Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system

The term “tipping point” commonly refers to a critical threshold at which a tiny perturbation can qualitatively alter the state or development of a system. Here we introduce the term “tipping element” to describe large-scale components of the Earth system that may pass a tipping point. We critically evaluate potential policy-relevant tipping elements in the climate system under anthropogenic forcing, drawing on the pertinent literature and a recent international workshop to compile a short list, and we assess where their tipping points lie. An expert elicitation is used to help rank their sensitivity to global warming and the uncertainty about the underlying physical mechanisms. Then we explain how, in principle, early warning systems could be established to detect the proximity of some tipping points.

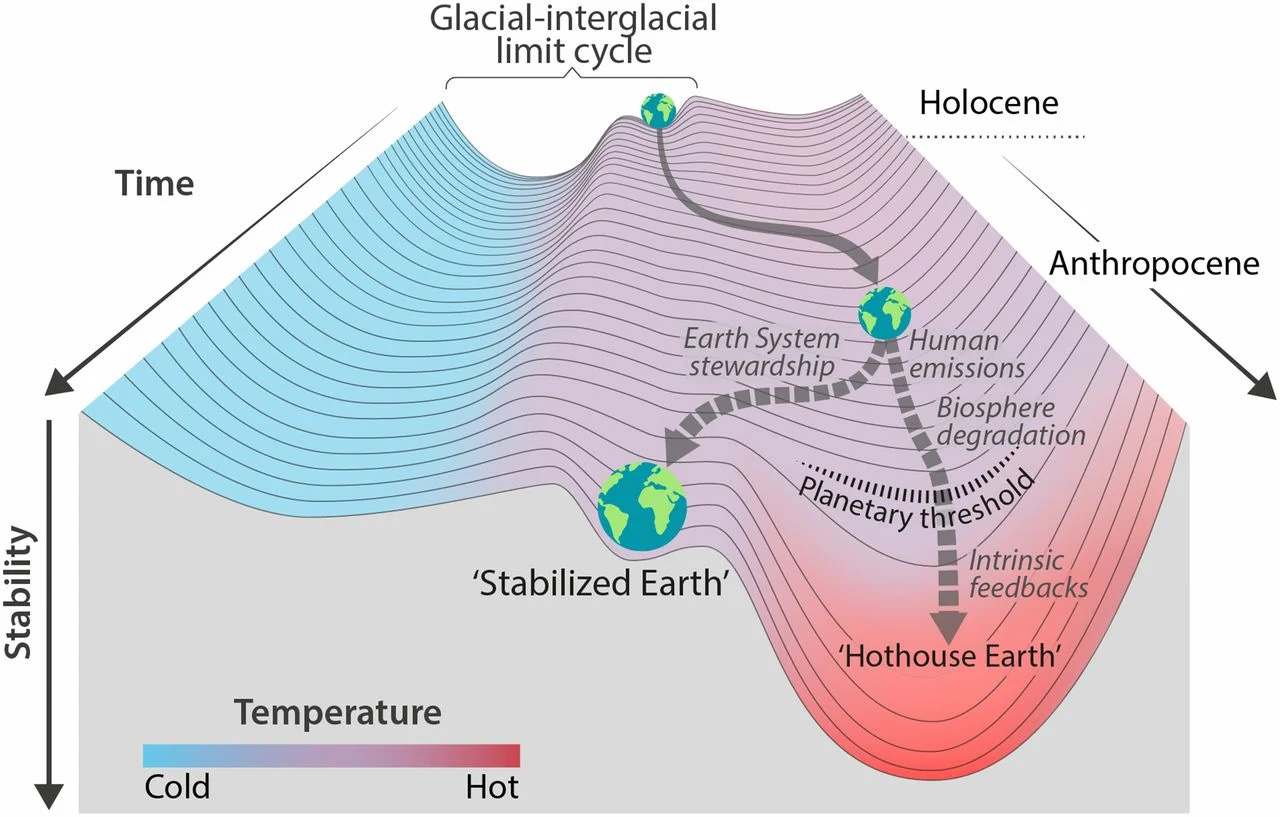

Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene

We explore the risk that self-reinforcing feedbacks could push the Earth System toward a planetary threshold that, if crossed, could prevent stabilization of the climate at intermediate temperature rises and cause continued warming on a “Hothouse Earth” pathway even as human emissions are reduced. Crossing the threshold would lead to a much higher global average temperature than any interglacial in the past 1.2 million years and to sea levels significantly higher than at any time in the Holocene. We examine the evidence that such a threshold might exist and where it might be. If the threshold is crossed, the resulting trajectory would likely cause serious disruptions to ecosystems, society, and economies. Collective human action is required to steer the Earth System away from a potential threshold and stabilize it in a habitable interglacial-like state. Such action entails stewardship of the entire Earth System—biosphere, climate, and societies—and could include decarbonization of the global economy, enhancement of biosphere carbon sinks, behavioral changes, technological innovations, new governance arrangements, and transformed social values.

Ambiguity of early warning signals for climate tipping points

There is concern that climate change might lead to abrupt and irreversible changes in parts of the Earth system at so-called tipping points. Theoretical considerations suggest that statistical measures can be used to detect early warning signals (EWSs) for reduced resilience, which could be interpreted as an increased proximity to climate tipping points. Here we discuss limitations of commonly used EWSs and their detection and discuss how alternative explanations can lead to resilience loss in the absence of tipping points. We argue for better testing of the existence of tipping points, beyond the application of EWSs, and propose a method to better quantify the probability of approaching tipping points using EWSs.

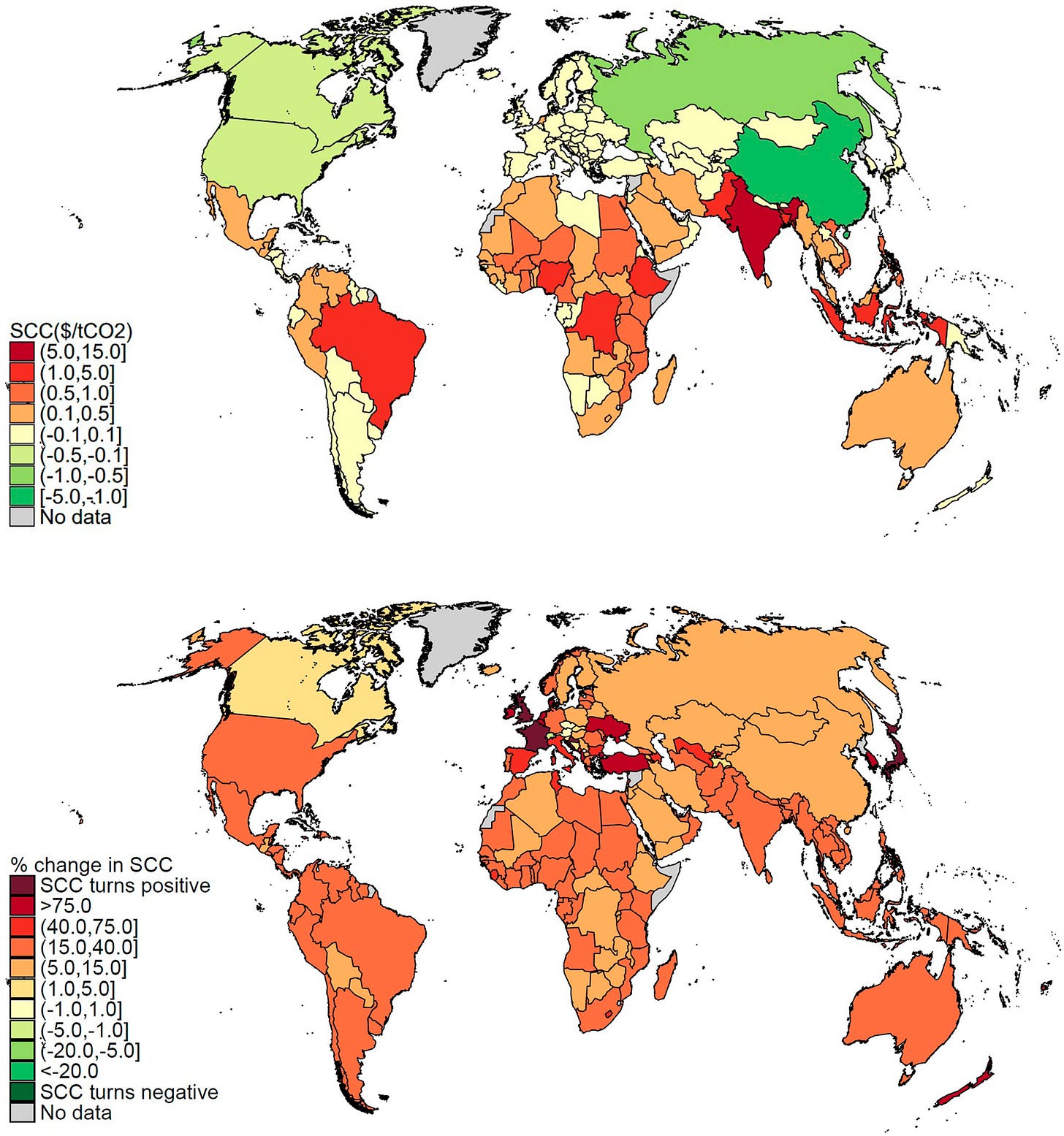

Economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system

Climate scientists have long emphasized the importance of climate tipping points like thawing permafrost, ice sheet disintegration, and changes in atmospheric circulation. Yet, save for a few fragmented studies, climate economics has either ignored them or represented them in highly stylized ways. We provide unified estimates of the economic impacts of all eight climate tipping points covered in the economic literature so far using a meta-analytic integrated assessment model (IAM) with a modular structure. The model includes national-level climate damages from rising temperatures and sea levels for 180 countries, calibrated on detailed econometric evidence and simulation modeling. Collectively, climate tipping points increase the social cost of carbon (SCC) by 25% in our main specification. The distribution is positively skewed, however. We estimate an 10% chance of climate tipping points more than doubling the SCC. Accordingly, climate tipping points increase global economic risk. A spatial analysis shows that they increase economic losses almost everywhere. The tipping points with the largest effects are dissociation of ocean methane hydrates and thawing permafrost. Most of our numbers are probable underestimates, given that some tipping points, tipping point interactions, and impact channels have not been covered in the literature so far; however, our method of structural meta-analysis means that future modeling of climate tipping points can be integrated with relative ease, and we present a reduced-form tipping points damage function that could be incorporated in other IAMs.

Machine learning-based techniques

Early Predictor for the Onset of Critical Transitions in Networked Dynamical Systems

Numerous natural and human-made systems exhibit critical transitions whereby slow changes in environmental conditions spark abrupt shifts to a qualitatively distinct state. These shifts very often entail severe consequences; therefore, it is imperative to devise robust and informative approaches for anticipating the onset of critical transitions. Real-world complex systems can comprise hundreds or thousands of interacting entities, and implementing prevention or management strategies for critical transitions requires knowledge of the exact condition in which they will manifest. However, most research so far has focused on low-dimensional systems and small networks containing fewer than ten nodes or has not provided an estimate of the location where the transition will occur. We address these weaknesses by developing a deep-learning framework which can predict the specific location where critical transitions happen in networked systems with size up to hundreds of nodes. These predictions do not rely on the network topology, the edge weights, or the knowledge of system dynamics. We validate the effectiveness of our machine-learning-based framework by considering a diverse selection of systems representing both smooth (second-order) and explosive (first-order) transitions: the synchronization transition in coupled Kuramoto oscillators; the sharp decline in the resource biomass present in an ecosystem; and the abrupt collapse of a Wilson-Cowan neuronal system. We show that our method provides accurate predictions for the onset of critical transitions well in advance of their occurrences, is robust to noise and transient data, and relies only on observations of a small fraction of nodes. Finally, we demonstrate the applicability of our approach to real-world systems by considering empirical vegetated ecosystems in Africa.

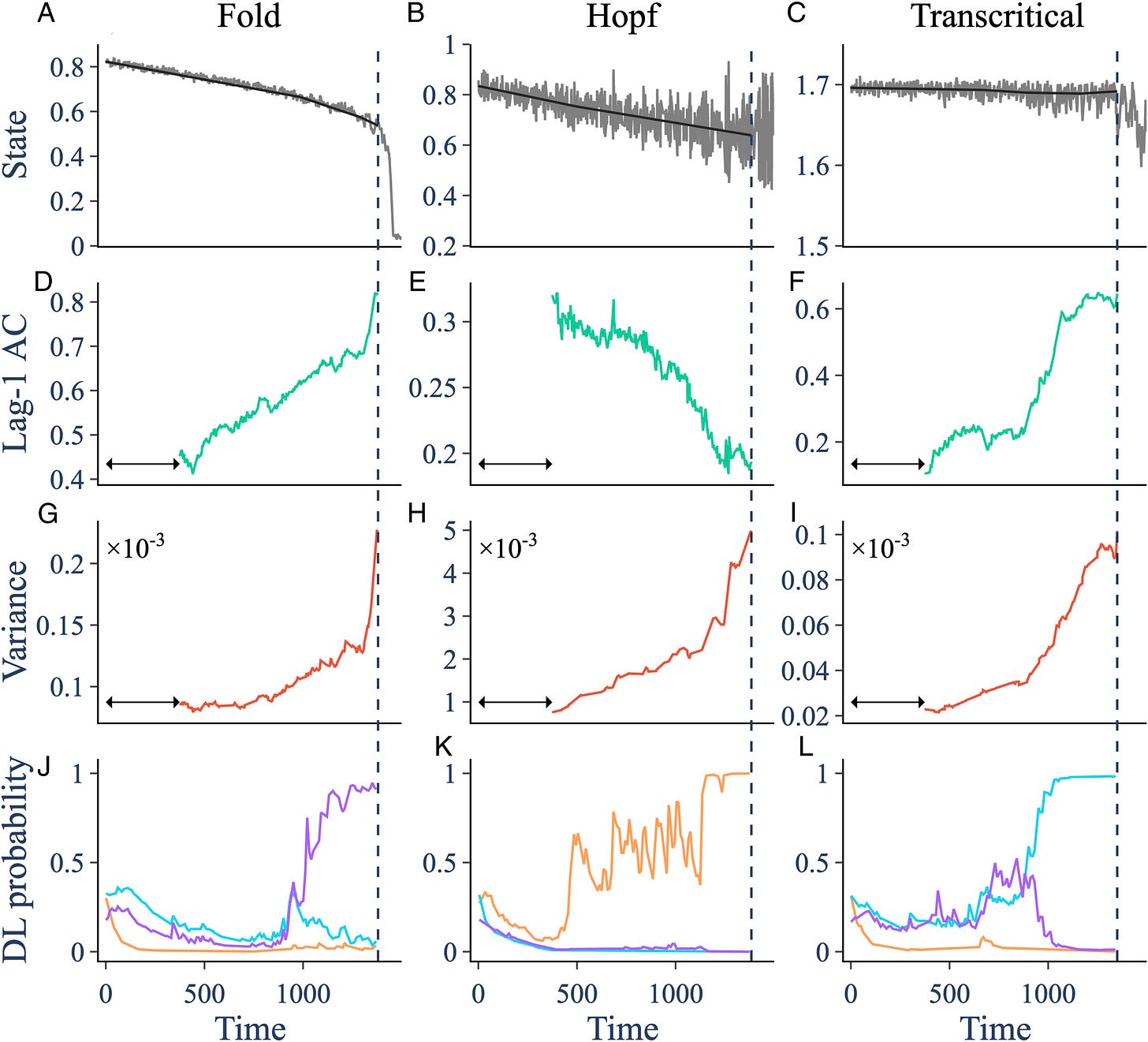

Deep learning for early warning signals of tipping points

Early warning signals (EWS) of tipping points are vital to anticipate system collapse or other sudden shifts. However, existing generic early warning indicators designed to work across all systems do not provide information on the state that lies beyond the tipping point. Our results show how deep learning algorithms (artificial intelligence) can provide EWS of tipping points in real-world systems. The algorithm predicts certain qualitative aspects of the new state, and is also more sensitive and generates fewer false positives than generic indicators. We use theory about system behavior near tipping points so that the algorithm does not require data from the study system but instead learns from a universe of possible models.

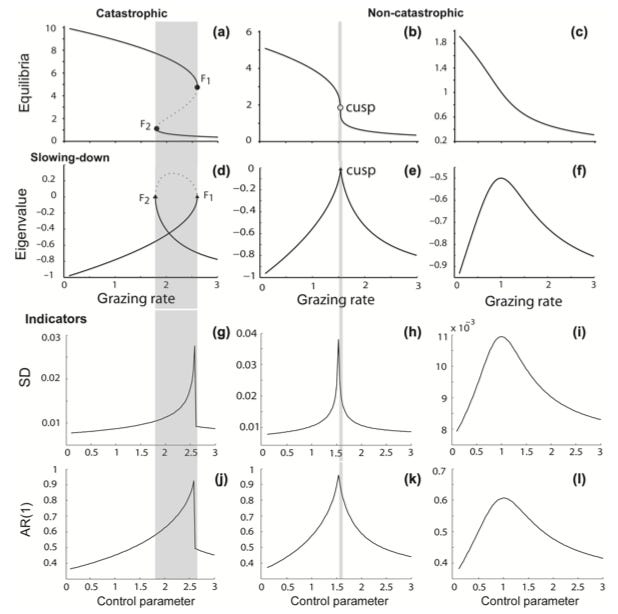

By considering three distinct classes of bifurcations, namely:

this paper nicely summarizes some of the results related to the paper by Scheffer et al mentioned at the beginning of this post

Many natural systems exhibit tipping points where slowly changing environmental conditions spark a sudden shift to a new and sometimes very different state. As the tipping point is approached, the dynamics of complex and varied systems simplify down to a limited number of possible “normal forms” that determine qualitative aspects of the new state that lies beyond the tipping point, such as whether it will oscillate or be stable. In several of those forms, indicators like increasing lag-1 autocorrelation and variance provide generic early warning signals (EWS) of the tipping point by detecting how dynamics slow down near the transition. But they do not predict the nature of the new state. Here we develop a deep learning algorithm that provides EWS in systems it was not explicitly trained on, by exploiting information about normal forms and scaling behavior of dynamics near tipping points that are common to many dynamical systems. The algorithm provides EWS in 268 empirical and model time series from ecology, thermoacoustics, climatology, and epidemiology with much greater sensitivity and specificity than generic EWS. It can also predict the normal form that characterizes the oncoming tipping point, thus providing qualitative information on certain aspects of the new state. Such approaches can help humans better prepare for, or avoid, undesirable state transitions. The algorithm also illustrates how a universe of possible models can be mined to recognize naturally occurring tipping points.

→ Please, remind that if you find value in #ComplexityThoughts, you might consider helping it grow by subscribing, or by sharing it with friends, colleagues or on social media. See also this post to learn more about this space.